At a Manchester bog, conservationists are still battling the damage of the Industrial Revolution

A toxic legacy lies beneath the surface of Holcroft Moss. What does that mean for its future?

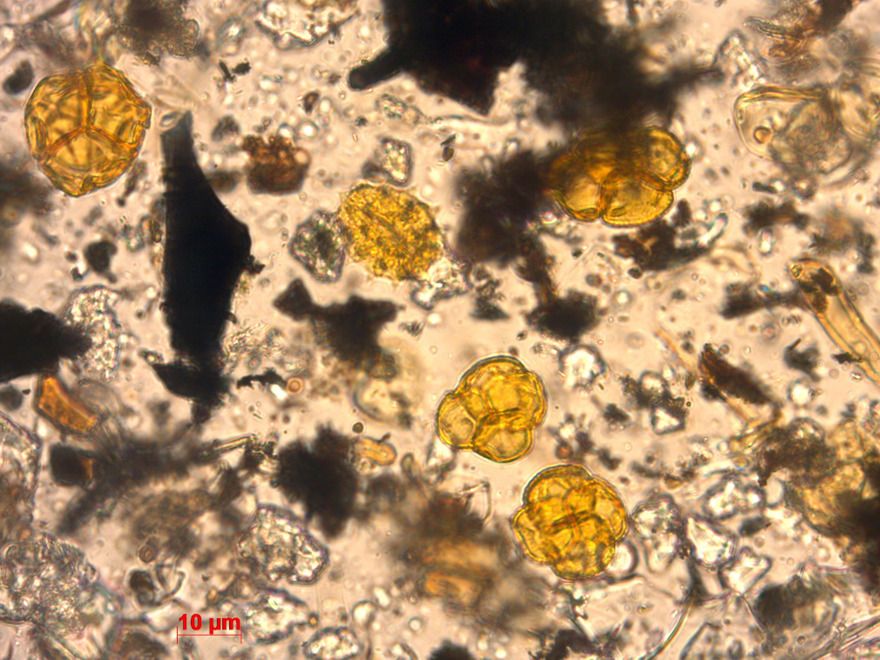

On the screen is a photograph: an extreme close-up, snapped through a microscope, of a sliver of peat.

The translucent particles suggest a kaleidoscope image than a portrait of an historic bog. But that is what this picture shows. The amorphous shapes represent the landscape of Holcroft Moss, a flat expanse of peat poised between Manchester and Liverpool, just as it would have looked around two centuries ago.

Translating these shapes into something visually comprehensible requires the help of an expert. Will Fletcher, a palaeoecologist at the University of Manchester, is as fluent in the language of sediment as they come. His research usually focuses on the ancient landscapes of the Mediterranean and North Africa. His decision to investigate the recent history of a local bog represents something of an unglamorous departure from that speciality, but the tools of interpretation are much the same.

The golden blobs that float through the centre of the photograph, he explains, are grains of pollen. They drifted from the plants that were growing at the moment this particular sliver of peat was formed, preserved where they landed by the oxygen-starved, acidic conditions of the bog. “This is something in the daisy family,” he says, gesturing towards one of the blobs. “You can see some heather pollen here. That looks like grass pollen up there.”

Nothing unusual there. But those golden blobs are in the minority, obscured by the black smudges and transparent shards of some less expected particles. It is as though someone has broken a beer glass and stubbed out a cigarette within the frame – which is actually not so far from the truth.

These are the bits of charcoal, silica and whatever else happened to be billowing out of Manchester’s smokestacks at the time of the Industrial Revolution – a sludgy reminder, just below the surface, of the persistence of our environmental impacts. There are traces of lead and copper too, although they are too small to be seen through the microscope.

“It’s a highly toxic layer to this day,” says Fletcher.

Holcroft Moss is a special place, but only by historical accident. It sits within a wider patchwork of lowland raised bogs, known as the Manchester Mosses, stretching across northwest England. However, while the other bogs were stripped of their upper layers by peat-cutters during the twentieth century, Holcroft Moss somehow remained intact, offering a unique archive of environmental change right up to the present day.

The slice of peat beneath the microscope represents just a small part of the core that was extracted from Holcroft Moss in 2015. Altogether, that core contains around 700 years of history. It reveals that this was no static ecosystem, but rather a shifting landscape of heather, sedges, trees and sphagnum mosses, growing in varying proportions according to the frequency of fire, rainfall and grazing activity.

Some of the shifts in vegetation were natural. Holcroft Moss was not alone in becoming boggier and mossier around 1650, for instance – bogs in Northern Ireland and the Cairngorms became wetter around this time too, indicating a general change in the weather. Other shifts, such as the rise in heather due to increased fire during the 1500s, were likely influenced by human interference, including an increase in grazing cattle.

All of these changes, however, require special equipment to detect: for most of its fifty centimetres, the peat core remains a uniform muddy brown.

The impacts of the Industrial Revolution, on the other hand, are easily detected by the human eye. Decades of pollution have dyed the uppermost layer of Holcroft Moss a deep sooty black. In this toxic concoction can be read a blow-by-blow account of industrialisation, and its devastating impact on the natural world.

Copper levels, for instance, jumped following the revival of smelting after the English Civil War; again with the establishment of the Bank Quay Copper Works at Warrington in 1717; and again when regional smelting increased after the output from Welsh mines declined. Lead and charcoal contamination rose alongside the combustion of fossil fuels, tracking the rise of major industries – including salt boiling, sugar baking, glass making and beer brewing – and the construction of the canals and railways that enabled their growth. Dust, too, increased sharply at the end of the 19th century, with the construction of Wigan Junction Railway directly through the bog.

The pollution changed the ecology of the bog. One contemporary, writing in 1882, observed how “fruitful vales where vegetation flourished… have been changed by the deleterious compounds of coal-smoke into barren deserts.” Sensitive sphagnum mosses were the first to suffer – their decline began in the mid-18th century. Heather replaced the sphagnum, and then grasses replaced the heather. Coal smoke inhibited the growth of trees and shrubs that would once have dotted the peatland.

The depredations of the 20th century have exacerbated the problems that were initiated by the Industrial Revolution. Continued agricultural conversion, drainage and peat-cutting at nearby bogs have lowered the water table at Holcroft Moss. Although air pollution has improved since the industrial heyday, the construction of the motorway on the northern border has added new pollutants to the mix and severed the site from its surroundings.

Dried out and disconnected, Holcroft Moss is now a shadow of its former self, its ecology unprecedented in the last 700 years. Where there was once a shifting tapestry of heather and moss, today there is only purple moor-grass, Molinia caerulea, one of the few species able to thrive in such conditions, and which therefore crowds out the more delicate plants.

After centuries of abuse, the bog is now in the care of conservationists. Cheshire Wildlife Trust is working to improve the hydrology of the site, using sheets of plastic to retain rainfall and grazing a small number of Hebridean sheep to reduce the dominance of moor-grass. But when it comes to the toxic legacy beneath the surface, there is little to be done.

“We are fighting history,” says Kevin Feeney from Cheshire Wildlife Trust. “We are very limited on what we can do at Holcroft Moss. We can do a lot of habitat management, we can keep the tree cover down, but we are fighting a legacy of the past.”

Short of stripping the top layer of peat from the bog in its entirety – something that is neither achievable nor desirable across such a large area – it may be that patience is the best approach to returning the more delicate species to the site. “Peat forms in layers,” Feeney points out, “so it could take a hundred years before that infected layer becomes deep enough that it stops being a problem.”

But the message of Fletcher and his colleagues’ research is not that conservationists should give up on Holcroft Moss entirely. Buried within the sediments is also an important lesson in building resilience: the peatland may be better able to withstand the hotter, drier conditions of the future if heather is allowed to make a comeback.

The plant is almost absent from Holcroft Moss today, but pollen records show that it was abundant during long periods of the past, back before humans had significantly altered the habitat.

Heather advanced during the decades of naturally drier weather, when the bog was more fire-prone, and retreated as wetter weather set in. These fluctuations were the bog’s way of adapting to an unstable climate – a world apart from the intentional creation of heather monocultures that are sometimes cultivated in the uplands today in the interests of driven grouse shooting.

Now, thanks to human-induced climate change, future conditions are more likely to resemble these hotter and drier periods of history. When it comes to peatland restoration, conservationists often focus on re-establishing sphagnum mosses, explains Fletcher, but the return of heather, in this case, would be an equally worthy goal – one that takes into account both future resilience and the potential challenges of re-growing the sensitive sphagnum mosses in the contaminated soils.

“If you can get the moisture levels up, but you have a fluctuating balance of heather and sphagnum, that could be a good outcome for this site [and] actually consistent with the natural history,” he says. “Perhaps there’s a message that needs to get out about the diversity of vegetation that could exist on healthy bog systems. We need to be open-minded about that.”

Ultimately, the efforts to restore Holcroft Moss must extend beyond the boundaries of the site itself, says Feeney. Time may undo some of the damage from the past, but only if modern humans stop inflicting new harms.

“It will only get back to pre-industrial health if we take air quality and water quality seriously, and get it as clean as possible,” says Feeney. “Whether we can ever get it back at that level is another question. But I think nature can heal all if it’s allowed to.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.