“At its root, rewilding is an ecocentric approach.”

Future Land: An interview with Steve Carver, director of the Wildland Research Institute, on wilderness and rewilding.

Today's feature is part of our Future Land series. You can read the full transcript here.

Future Land is a series focusing on the people who are shaping the conversation around nature and conservation in Britain today. We carry out in-depth interviews, and publish the transcript in full, alongside a shorter feature. Conversation is encouraged: you can post comments at the bottom of the article.

The full transcript is only available to paid members of Inkcap Journal. To join, click here. You'll also receive our popular digests of the week's nature news.

What does it mean to be wild, in a world where pristine wilderness no longer exists?

For Dr. Steve Carver, a geographer at the University of Leeds, wildness exists on a spectrum: something never quite perfect or absolute, but that can nonetheless thrive between the numberless fingerprints of humanity. It is a quality that increases as the road fades out of sight, and diminishes as ecosystems are interrupted by outside forces.

"It harks back to Roderick Nash’s book, Wilderness and the American Mind," says Carver. "He comes up with this notion of the wilderness continuum, the ‘paved to the primeval’, indicating that there is this spectrum of human modification of the landscape: from city centre environments through to pristine wilderness, if such a thing exists anymore, through all of the intervening levels of human modification in between – from farmland to semi-natural to wildlands to wilderness."

Carver has made a career out of mapping these wild areas, such as they are. His speciality is GIS – Geographic Information Systems – a computer-based method of visualising and analysing spatial information about the real world. He started out by mapping suitable storage locations for radioactive waste, but a love of mountaineering and the outdoors caused him to pivot towards wilderness mapping instead.

Today, he is director of the Wildland Research Institute, where he focuses on both wild land mapping and rewilding policy.

Drawing the boundaries of wilderness onto a map is contentious territory for any academic – who, after all, gets to decide what is wild? – and for many years Carver was reluctant to display his findings in such a binary fashion. “To put a line on the landscape and say, ‘This is wild and this isn’t,’ is false, really, because it's essentially where you draw that threshold,” he says.

In Scotland, where memories of the Highland Clearances still haunt lives and the landscape two centuries on, the concept of wilderness is particularly controversial.

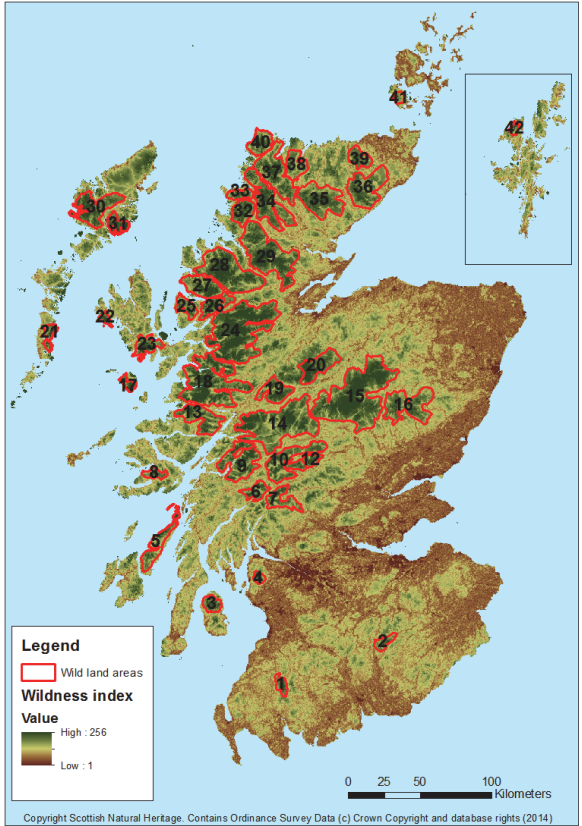

Nonetheless, in 2014, Scottish Natural Heritage (now NatureScot) used Carver’s methodology to map 42 Wild Land Areas, covering nearly 20% of Scotland, mostly in the north of the country. The agency defined these as awe-inspiring places with a high degree of naturalness and a lack of human artefacts; today, they are considered nationally important in Scottish planning policy, which states that they have “little or no capacity to accept new development”.

This mapping exercise has evoked both enthusiasm and resentment. For the John Muir Trust, it was celebrated as a breakthrough moment in helping to protect wild land from industrial developments. For others, however, the emptiness of the landscape serves as a reminder of a brutal history, rather than an aesthetic quality to be celebrated and protected. Some have criticised the maps for focusing on Romantic era notions of savage, rugged beauty, rather than any special ecological traits.

Carver believes that the Wild Land Areas were “perhaps a little bluntly defined”, but that the regions are a mixed bag when it comes to historical population patterns. “If you map the patterns of pre-Clearance settlement and the archaeological record, then yes, there are parts of those Wild Land Areas which have clearly held pretty high numbers of people in the past, and have been subsequently cleared; so those are those ‘emptied’ landscapes,” he says.

“Yet there are other parts of those Wild Land Areas which never really afforded a living for people – they’re just simply too climatically limited and rugged and remote for people to live in. We're talking central core areas above 300, 400 metres in altitude: there's no living, and never was a living, to be made in those landscapes. They were known; people travelled through them, drove their cattle and sheep to market through and hunted in them, but they were still wild land. They were not settled or farmed. So it's all about nuance.”

Humans, in the western world at least, have long seen wilderness as a place to be fenced off and preserved – a diminishing resource to be protected in the face of expanding settlements and farmland. That perspective is changing: increasingly, conservationists and landowners have seized upon the idea of rewilding as a way of creating wilderness – or at least a simulacrum of it – on land that has been tamed or degraded.

Carver is at the forefront of this conversation. He is co-chair of the IUCN's rewilding group, which works to streamline the theory and practice of rewilding at an international level. Earlier this year, he published a paper setting out ten guiding principles for rewilding, cognisant of the way in which the term has been altered and arguably diluted since it emerged in the 1980s.

“The ultimate aim of rewilding, in my mind, is to generate secondary wilderness. We're giving that space and that time – and that's a crucial element – back to nature to allow nature to determine outcomes. And in traditional conservation, that's not what we do,” he says.

Refusing to mow your lawn is not rewilding, he stresses, no matter how beneficial to pollinators. But despite his refusal to countenance some of the more liberal applications of the term, Carver believes that rewilding, like wilderness, takes place on a continuum.

He is unconvinced that Britain has witnessed the resurgence of anything truly wild, and believes that Knepp’s rewilding efforts, for instance, are undermined by the fact that the estate sits within an intensely farmed and densely populated landscape. In comparison, Carrifran, a reforestation project in the Moffat Hills, is "by far on the wilder end of the spectrum".

For Carver, the beating heart of rewilding is the intrinsic value it ascribes to nature itself. Nature, he believes, should be unfettered from humanity's guiding hand not because homo sapiens stand to gain, but for nature's own sake.

“One of the problems I've seen with some of the thinking about rewilding at the moment is that it’s sort of an anthropocentric vision of nature's benefits for humans,” says Carver.

“I know to some extent you've got to take those into account to sell the concept to politicians and decision-makers. And recently we've seen the Dasgupta Review, reassessing the position of nature within capitalist systems. But I think at its root, rewilding is an ecocentric approach, and it has resonance within E.O. Wilson's Half Earth concept – that if the planet is to be sustainable, we need to give space back to nature.”

While he stresses that rewilding will never be about removing people from the landscape, it does involve reassessing the relationship between nature and culture. He describes the history of human endeavour as a “temporary veneer” upon a canvas shaped by much older forces: glaciers, rivers, oceans and geology. “You can't keep everything in aspic, is what I’m trying to say.”

Rewilding recognises that nature, too, is dynamic. The idea of returning to a past ecological state is a "bit of a misnomer", he says, while biodiversity is a "coarse measure of success". Rather, the focus should be on the bigger picture, including the relationships and interactions that emerge between the different elements of the ecosystem. It is this, he says, that sets rewilding apart from traditional nature conservation activities.

“In a lot of instances, protected areas, nature reserves and designations are deemed to be failing because they have changed from the reasons they were originally designated into something else,” he says.

“It’s the nature of a lake to start to fill with sediment; and that lake becomes a reed bed, and it's the nature of a reed bed to dry out and become a raised bog; and the nature of a raised bog to dry out and become dry heath; and that heath becomes forest.

“And yet we intervene all the time and say, 'Oh, no, that's not right. It wasn't originally protected as a birch forest; it was protected initially because it was a dry heath.' But nature evolves… I see the value of protecting key habitats of species, don’t get me wrong, but I think in certain places where it’s possible we need to step back and let nature call the shots.”

And is there room for reintroduced species – for large mammals, or for wolves and lynx – in these rewilded landscapes of the future? For Carver, it’s not a question of ‘if’ so much as ‘how’; a balance between an overly cautious approach that fails to deliver, and a gung-ho attitude that ultimately disenchants people with the whole idea.

“This notion of buying some lynx from the continent, bringing them over in a yacht and then kicking them out of a white van in the Highlands somewhere is probably not a good way to go. But we've seen how illegal or accidental releases of species like beaver have moved things along,” he says.

Britain is an island, and therefore most reintroductions will have to be undertaken on purpose; unlike our neighbours on the continent, we cannot simply wait for new creatures to spread naturally into restored territory. This is something of an bureaucratic and social obstacle.

Yet despite a faltering start to lynx reintroductions – an effort to reintroduce the big cat to Northumberland has faced repeated criticism for failing to adequately consider local concerns – Carver believes that its return to Britain is possible within his own lifetime.

Wolves, not so much. But if the island is uniquely unsuited to this predator, it’s not down to ecology so much as its people. “There are wolf populations in Denmark, in Belgium even, and you’ve just got to question why they are not in the UK. Well, they’re not in the UK because of our attitudes,” he says.

“In many respects, in terms of conservation, we’re a small island nation with a small island mentality.”

To read the full transcript – including discussion on the Vera Hypothesis, cultural severance, and more – click here.

Our independent environmental journalism is entirely funded by readers. To become a member – and to receive our weekly news digest – click here.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.