Beautiful but dying: Inside the fight to save Lake Windermere

For 41 weeks straight, Matt Staniek has sat outside a United Utilities office and demanded action. What more will it take to save the Lake District's most famous lake?

Every Monday morning, at 9am, a group of activists gathers outside the United Utilities information centre in the heart of the Lake District. There are the usual protest placards, but also poo-shaped hats, and occasionally, an entire ceramic toilet.

This is a ‘sewage strike’: a protest against the local water company, which campaigners say has been dumping millions of litres of sewage into the surrounding catchment.

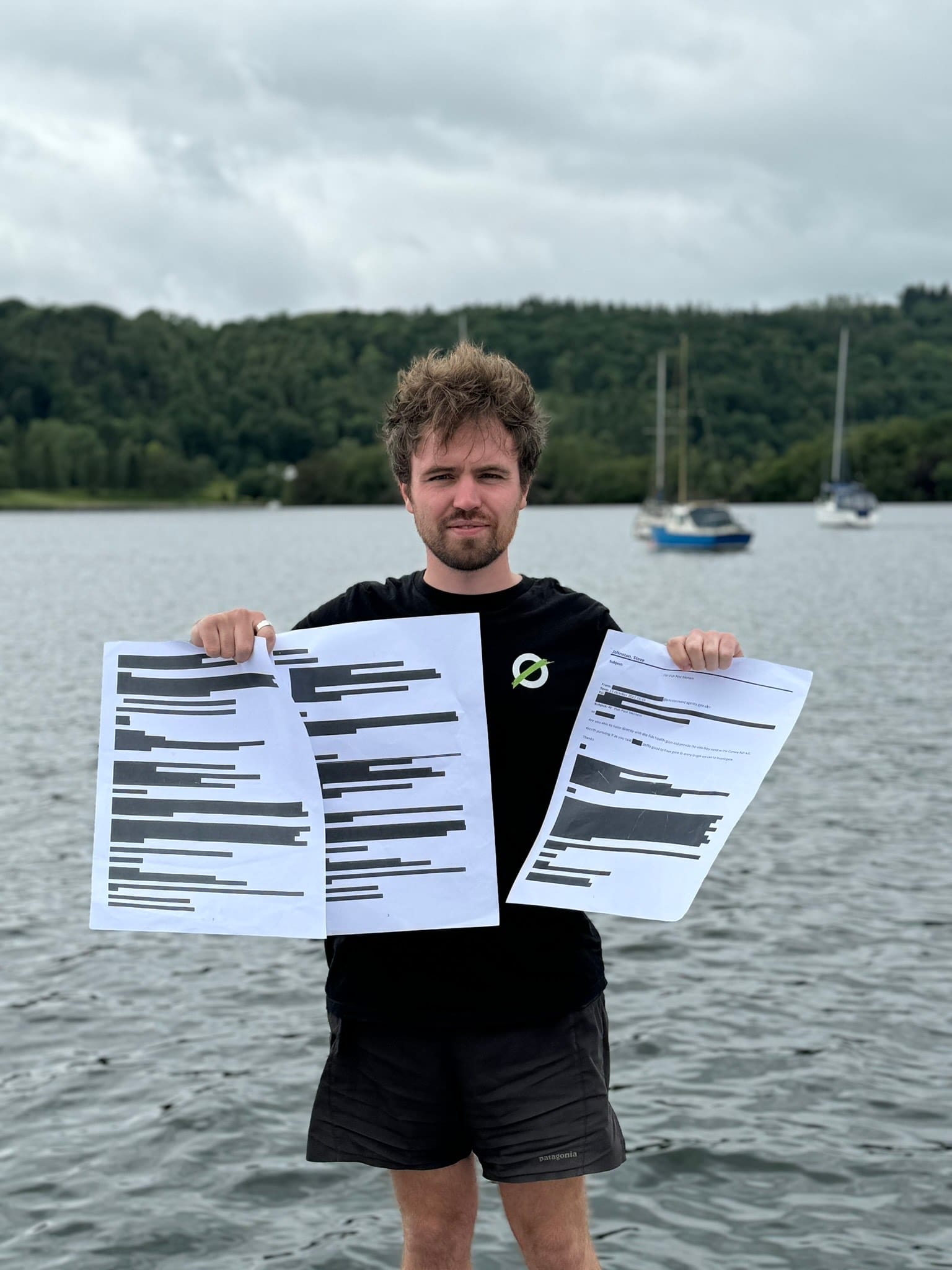

So far, the protest has been going for 41 weeks straight. The company in attendance tends to change each week, except for one face. Matt Staniek, dressed in his trademark shorts and t-shirt, is a constant presence.

Matt is the face and founder of Save Windermere, a campaign he started in 2021 to champion the deteriorating health of the iconic lake. Grown on the power of social media – and Matt’s sheer willpower – the campaign has reached millions of people, and put the local issue onto the national stage.

I first met Matt at an event in Parliament last summer, where he spoke passionately about how those in power are not doing enough to protect the country’s natural assets. Later, I catch up with him on the phone for a ‘proper chat’. The 28-year-old speaks in a frank and unreserved manner, and his energy and evident passion for the subject is contagious.

At Westminster, he had told me that ‘the fundamental truth is that not everything is rosy.’ Referring to the ministers present, he adds: ‘It’s okay for them to say here that they’re doing what they can, but on the ground it reflects a very different story.’

Lake Windermere is nestled in the heart of the Lake District. A ribbon of seemingly pristine freshwater stretching eighteen kilometres in length, it is England’s largest lake and one its most popular natural tourist attractions.

What is not apparent in the scenic photographs is that the ecosystem of the lake is sick – and deteriorating rapidly. In 2022, this hidden illness became shockingly visible when the entire northern basin turned a bright, insidious green. The giant toxic algal bloom was a disturbing indicator of what was happening beneath the surface.

There are few people who know more about the health of Windermere than Matt. He grew up on its shores, but he tells me that he was ‘completely naïve’ to its deteriorating state for years. It wasn’t until an accident drastically changed his life that he discovered the ‘stark reality’.

After Matt returned home from studying Zoology, he was involved in a car crash which broke his neck. He spent eight weeks in a neck brace, during which his mental health suffered. After the brace came off, he needed something to help the healing process.

‘Nature is what really gives me hope, it’s what inspires me, so I started going to the head of Windermere, which is somewhere that my gran took me when I was a kid,’ he tells me.

Matt spent three years visiting the same spot on the lakefront every day, and it was during this time that he witnessed a visible decline. ‘It was losing flagship species in front of my eyes,’ he recounts. ‘I would go down there and see a dipper on the same perch every morning, and then one day I go down and it’s gone. You won’t see dippers fishing now below Ambleside wastewater treatment works.’

Matt began digging into the issue, and what he discovered was sewage. And lots of it.

The first clue came from research by the Rivers Trust, which revealed that, in 2020, over 7,000 hours of untreated sewage had been discharged into the Windermere catchment. It doesn’t take a freshwater ecologist to figure out that tonnes of raw sewage isn’t good for the health of a lake, but in the case of Windermere, it is particularly critical.

Windermere is an oligotrophic lake, meaning it is naturally very low in nutrients. It is also a slow and enclosed water system: it takes a drop of water nine months to travel from the head of the lake to the bottom, so any pollutants which enter tend to stick around.

In the case of untreated sewage – which contains high levels of nutrients such as phosphorus – years of input have created a latent layer of nutrient-rich sediment on the bed of Windermere. Combined with factors such as high temperatures or droughts, this can fuel extensive algal outbreaks. Testing during summer months revealed that, pound for pound, the algae present in Windermere had higher levels of toxicity than cobra venom.

Since launching the campaign, Matt has recorded – and personally witnessed – the impact of pollution on Windermere’s non-human residents. He describes the decimation in grim figures. The number of sea trout caught on the River Leven, Windermere’s main outlet, plummeted from 850 individuals in 1980 to just 12 in 2021. Meanwhile, Arctic charr – a flagship species which has inhabited the lake since the last Ice Age – is thought to be extinct in the south basin of Windermere, and its future in the north basin remains precarious.

Matt himself has documented the repercussions of sewage spills, including a mass fish kill on Cunsey Beck, which he believes was caused by discharges misreported by United Utilities. He witnessed scores of rare and protected species – including Atlantic salmon, white-clawed crayfish and river eels – perish in the river.

At the lower end of the food chain, the campaign has also recorded significant reductions of invertebrates living in Windermere tributaries, from above to below wastewater works. In February, testing results revealed a 75% reduction of pollution-sensitive riverfly species in the Welfin Beck, and a 64% reduction in the River Rothay.

Matt explains that monitoring the resident wildlife can reveal some of the longer-term impacts of sewage pollution. Whereas a water sample will only show what’s happening in the river at any given moment, ‘invertebrates are there all the time, absorbing what's going into the water. So they're essentially the canaries in the coal mine to this situation.’

These canaries are sounding the alarm. The current state of the lake is already alarming, but something even more devastating is on the horizon. The summer of 2022 saw the first ever 40 degree day in the UK, and climate change could cause these temperatures to become common in the Lake District. ‘The lake is simply not adaptable to that threat,’ Matt says.

Hot summer temperatures would likely coincide with peak tourist season, when sewage infrastructure is under the most pressure. Save Windermere recently teamed up with the UK Space Agency to map pollution inflows into Windermere. By cross-referencing phone data with satellite imagery, the project found a direct correlation between visitor numbers and algal spikes in the lake.

The impacts of climate change are not restricted to heat. Over the last year alone, unprecedented rainfall has increased the amount of sewage being discharged into the lake. ‘All of a sudden you’ve got this circumstance where all of the pressure points line up, and that could lead to something catastrophic like a mass fish death.’

The obvious question is – what can be done about it? According to Matt, there is an equally glaring answer: stop the sewage.

For the past three years, Save Windermere has been campaigning for the complete removal of all treated and untreated sewage released into the Windermere catchment. The direct ability to prevent discharges lies with the private companies who own and operate the infrastructure. Their focus is on United Utilities, the company responsible for the area. Performance data reveals that, since 2020, it has discharged more than 27,000 hours of untreated sewage into the catchment.

Most of this is legal spillage through ‘storm overflows’, which are designed to act as a relief valve to prevent the system being overwhelmed. However, data uncovered through Environmental Information Regulations requests has identified illegal spilling at Windermere catchment treatment works since 2022.

Last year, a BBC Panorama investigation revealed that untreated sewage had been illegally dumped into the middle of Windermere, and that the Environment Agency had failed to conduct a proper investigation into the incident. In May this year – just over a year after the original incident – the same thing happened, with over 10 million litres of raw sewage released illegally into the lake.

Campaigners are calling on the Environment Agency to step up. It is their responsibility to investigate and prosecute illegal breaches, and so far more than 100,000 people have signed a petition by Save Windermere for a public enquiry into the Agency’s failure to regulate United Utilities’ actions within the Lake District National Park.

Matt also thinks that Park authorities should be given more powers and resources, and that their actions should be overseen by an independent chair to ensure nature remains a priority amid the conflicting interests of multiple stakeholders.

Then there are the politicians themselves: the campaign has recently published a 10-point plan to save Windermere, calling on the new government to grant greater protection for the lake and ensure existing legislation is enforced. It also includes long-term measures to advocate for a Rights of Nature approach, recognising Windermere as a legal entity in its own right.

‘You’ve got infrastructure that cannot cope with the amount of people that are coming here,’ Matt explains. ‘And that’s simply down to the fact that we’ve not seen enough investment. And we’ve not seen innovative thinking to protect the lake.’

Matt often refers to the history of Lake Annecy in France. A glacial lake with two distinct basins, it is easily comparable to Windermere – although its local population is seven times the size. In the 1960s, the impact of sewage in Annecy was becoming evident through increased algal blooms and declines in fish populations. After an extended campaign by the community, however, the sewage was diverted by channelling it to treatment plants outside the catchment area. Now, Annecy is the cleanest lake in Europe.

‘That management has resulted in the lake being protected forever,’ Matt adds. ‘Whereas we’ve just had bits of investment every now and then. It’s been kicking the can further down the road.’

Since launching the campaign, Save Windermere has garnered more than 390,000 signatures on various petitions, and Matt’s charismatic videos documenting the ecological destruction have been viewed more than 19 million times.

Matt says he feels incredibly lucky to have grown up in the Lake District, and believes everyone has the right to immerse themselves in nature – but the health of the natural world must be protected first and foremost.

His fight is for Windermere, but Matt hopes that ultimately the campaign will have ramifications for aquatic ecosystems across the country.

‘The reason that this campaign has been helping to direct the national story is because this is the epitome of failings of government to protect our freshwater,’ says Matt. ‘Windermere is something that sits so close to not only residents and communities, but also the country, because so many people come here to see the natural beauty.’

Matt has invited all those who oppose the discharging of sewage into the lake to stand their ground with him and join the sewage strike. ‘The more people that are aware, the bigger the voice becomes,’ he says, ‘and the harder it is for those responsible to run away.’

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.