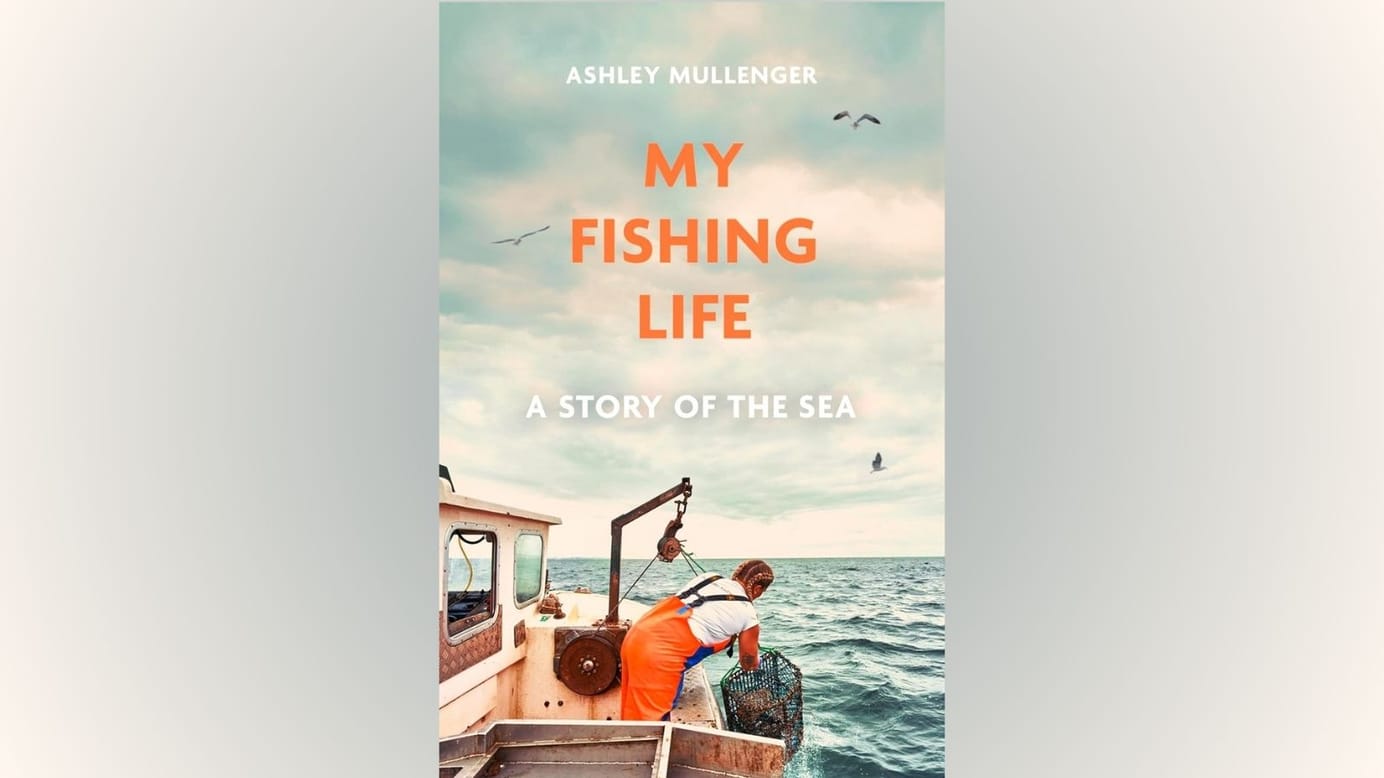

Book of the Month: My Fishing Life

Plus reviews of all the other books we read in May.

Books about Britain’s coasts and seas are common. Much less so are ones written by the people who spend more time than almost anyone else out there – commercial fishers.

The reason for that is obvious; fishers are far too busy fishing to pen memoirs. Step in Ashley Mullenger, an outspoken female fisherman (yes, she calls herself a ‘fisherman’). With support from a ghost-writer, My Fishing Life: A Story of the Sea is Mullenger’s invitation to us to step into her world.

My Fishing Life is not and does not set out to be nature writing, much like the last notable book on the subject, Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town by Lamorna Ash. Though there the similarity between the two books ends. Ash, while intrepid enough, was only ever a brief visitor onboard a Cornish bottom-trawler. And Dark, Salt, Clear often had the sense of being more concerned with the mechanics of prose than that of handling belligerent boat engines.

Mullenger herself was once a visitor. In her early twenties, a chance trip out of the office with colleagues led to her falling headlong in love with the fishing life. She became apprentice and crew to Nigel, owner of two vessels operating out of Wells-next-the-Sea in Norfolk. She learned to mend pots, bait with shickle (crab leftovers), sort with rapid-fire efficiency the whelks hauled from the depths, and navigate the tempestuous waters of maritime bureaucracy.

Mullenger focuses on how fishing is done. The nature in her book, while understated, is memorable and instructive. To harvest enough whelks, crabs, and lobsters to make a modest living, she needs to know where her quarry is and what it wants, which all depends on the time of year. We learn, for example, of the brown crab’s quirky mating migrations, and of the extraordinary longevity of lobsters – or as Mullenger describes them, ‘Ten-footed, navy-dappled, fan-tailed sea bugs.’

At the same time, Mullenger tracks her own progress as a woman shucking off some of the more suffocating trappings of modern life, and becoming a wilder version of herself, with the muck of the North Sea under her fingernails and her biceps swelling from the endless effort of hauling gear and crates. ‘The sea has liberated me,’ she writes, ‘Because she doesn’t give a shit what I look like.’

My Fishing Life is loosely structured around the efforts of her skipper, Nigel, to acquire new boats from distant ports in Scotland and Ireland when old ones need letting go. Sections of the book are thus travelogues, from Eriskay and Kilkeel respectively, tracking along coastlines and through lochs on the way back to Norfolk. These don’t hold the attention so well, although they do provide an opportunity for Mullenger to chart how different fishing communities across the British Isles have adapted again and again to target new species after the dwindling or total loss of formerly favoured stocks.

Which brings us to the matter of sustainability. Mullenger’s opinions are likely to make the nostrils of more than one environmentalist flare. She appeals: ‘Why don’t people understand that we fishermen are the guardians of our fish stocks precisely because if we don’t care for our oceans we will, inevitably, reap what we sow, and destroy our own, and our children’s and grandchildren’s, livelihoods?’

It’s a line that is so often heard from the fishing industry, but doesn’t always seem to ring true. Mullenger tells us that, while for brown crab there are no regulatory limits on how many can be caught, fishermen are still able to self-manage harvest rates – yet she neglects to mention that numbers of brown crab in UK waters appear to have plunged in recent years, with the Blue Marine Foundation asserting in late 2022 that ‘management shortfalls needed to be addressed before declines result in total collapse’ for stocks of this species in the UK.

Where Mullenger does offer substance to her claims of guardianship is the case of the mass crustacean die-off on the Teesside and North Yorkshire coasts, which occurred late 2021 and early 2022. Finding their pots suddenly empty or else filled with dead crabs, local fishermen soon came to a collective realisation that something was amiss. Defra and Cefas were called in, with the latter concluding from its investigation that an algal bloom was the main culprit. But fishing communities were and remain convinced that the crabs, lobsters, and countless other sealife were killed by releases of the chemical pyridine as a result of dredging during the development of the Teesside freeport.

Mullenger’s fishing livelihood is full of meaning, and wonder towards the natural world. But it’s also an exceptionally hard way of life, one which drains away the time and mental stamina that UK fishermen need if they’re to engage in dialogue and collaborate with fishery managers and environmental groups. ‘Why should fishermen trust the people with whom they should “co-manage” after so many decades of being shafted and lied to?’ the author asks – and by the book’s end, it’s hard to consider this an unreasonable question.

Mullenger sometimes seems to scorn the necessary complexities and compromises of sustainable fisheries management. Even so, her fervent plea for compassion is hard to ignore. At turns fun and frown-inducing, My Fishing Life is vital reading for anyone who wishes to have a voice when it comes to the future of the UK’s seas.

My Fishing Life: A Story of the Sea, by Ashley Mullenger. Published by Robinson, May 2024. Reviewed by Chantal Lyons.

Other books we read this month

The Light Eaters: The New Science of Plant Intelligence, by Zoë Schlanger, is a fascinating deep-dive into what it means to be a plant – viscerally, sensually, cerebrally. As much an exploration of the scientific process as of botany, it casts flora in a new light. Whether you agree with her conclusions may depend on how far you are willing to stretch metaphors of faunal sentience into the plant world. -SY

Bothy: In Search of Simple Shelter, by Kat Hill, is a nuanced and candid account of the author’s explorations of bothies across the UK. In equal measures travelogue, social history and nature writing, Hill questions what we seek from ‘wilder’ landscapes, and probes her own personal journey towards new purpose and the good life. -CG

Lost to the Sea: A Journey Round the Edges of Britain and Ireland, by Lisa Woollett, is a thoughtful and well-researched account of settlements and ecosystems that have been inundated by sea level rise. Woollett is a talented photographer, and it is a shame that the publishers have only included black-and-white photographs of the places she describes; some high quality images would have helped to bring the locations to life. -SY

Seaglass: Essays, Moments and Reflections, by Kathryn Tann, is a luminous collection of writing, based around the coastlines of Durham, South Wales and elsewhere. It is only partly nature writing – the ocean is more backdrop than subject – but essays such as The Nature of Change reveal a writer equally capable of addressing matters of ecology as the heart. -SY

Taking Flight: How Animals Learned to Fly and Transformed Life on Earth, by Lev Parikian, came out in paperback this month. Reading the prologue, I anticipated that its jokey tone would soon grate, but I was wrong. The science of flight is complex – this book delves into the depths of time and physics – but Parikian’s light touch means there is more joy here than head-scratching. -SY

Reviewed by Sophie Yeo and Coreen Grant.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.