Book of the Month: Understorey

Plus reviews of all the other books we read in June.

Weeds are an almost omnipresent part of nature, found in cities and countryside alike, yet they account for some of the most overlooked and undervalued of plants.

What would it mean to notice and appreciate them fully? And what would the effect be over an entire year of looking?

These are the questions that artist, writer and teacher Anna Chapman Parker set out to answer. Beginning in January, she spent a full year observing and drawing the weeds around her home in the north of England. The result is Understorey: A Year Among Weeds – a delicate and tender study of plants that rarely receive any attention.

Weeds are varyingly regarded as unimportant, disposable, or even undesirable in the realm of gardening. Chapman Parker touches on the ecological reasons for why weeds are valuable parts of their ecosystems – and notes the distinctive properties of the species she draws – but she is not an ecologist, and that is not the focus of her book.

Rather, Understorey offers a variety of botanical knowledge which is gained through intimate observation and interaction with weeds. Part diary, part sketchbook, it is a carefully kept record of the seasonal shifts as reflected in the detail of individual plants, observed from within touching distance.

As a working mother, Chapman Parker initially chose weeds as a subject of convenience: a way of being able to ‘just drop down and draw whatever was growing there’.

But after stumbling across a six-hundred-year-old painting of bindweed in the National Gallery, she began to look anew at the plants depicted in both classical masterpieces and growing on the pavement outside her house. She explains that ‘weeds were no longer accidental green stuff that didn’t matter: they were a living constancy, a kind of wild connective tissue across time and place. I wanted to know them better.’

None of the plants in Understorey are rare. But their commonality doesn’t make them any less remarkable to Chapman Parker. Through the extended process of looking and drawing, she comes to appreciate the tenacity, peculiarity, and surprising beauty of weeds, as well as the diversity of that ambiguous category.

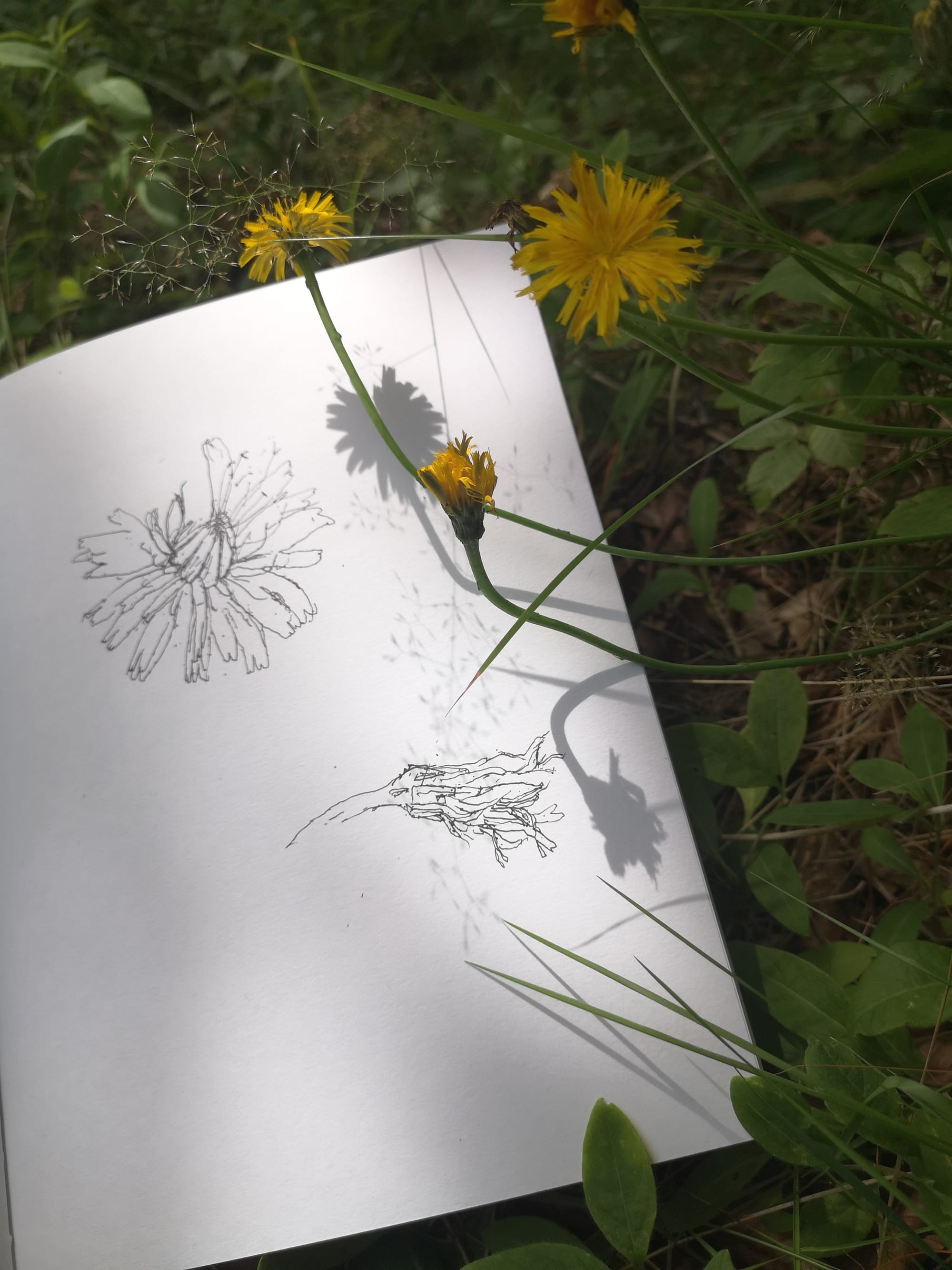

In the growing market of nature writing, the most original element of this new offering is Chapman Parker’s striking fine-line drawings, which are spread throughout the pages. The author dismissively describes her drawings as ‘very simple’, yet the intricate lines provide a vivid window into the unique character of each plant.

Drawn outdoors, the sketches feature smudges from raindrops, sprawling specimens which refuse to fit a neat frame, and even shifting perspectives as a flower opens during the time it takes to draw the rest of the plant. ‘Sometimes a “mistake” is a truthful record of change,’ she comments of the latter.

Like her drawings, the prose descriptions in Understorey are characterised by a deftness of touch. Some entries are short, rich snapshots: on October 3, she describes the ragwort that has gone to seed, the colours ‘mellowing exquisitely: soft, copper-brown spent flower bracts resemble tiny suns.’ Other entries delve deeper into the experience of drawing, from her self-consciousness of the public act of outdoor art, to the difficulty of capturing a particular feature to her satisfaction.

Alongside her own experience, Chapman Parker explores the depiction of weeds in other artworks. This ranges from the 1,500-year-old illustration of a bramble by the Greek botanist-physician Dioscorides, through to the the experimental use of cyanotypes by botanist Anna Atkins in the mid-19th century.

One passage explores the artwork of Maria Thereza Alves, who created a floating garden in Bristol planted with seeds excavated from local deposits of soil ballast from transatlantic slave ships. These deposits were ‘significant contributors to plant migration’, writes Chapman Parker, and Alves’ work ‘highlighted the capacity of plants to reanimate such histories.’

In the introduction to Nan Shepherd’s classic of nature writing, The Living Mountain, author Robert Macfarlane comments that: ‘We have come increasingly to forget that our minds are shaped by the bodily experience of being in the world. We are literally losing touch, becoming disembodied, more than in any previous historical period.’

If this is a true affliction of modern society, then Understorey is the perfect antidote. Drawing a spear thistle, Chapman Parker’s struggle to find clear ground to kneel ‘shows me how densely and prolifically they self-seed’.

This is the ‘bodily experience’ which Macfarlane describes: a physical relationship with the natural world, which Chapman Parker demonstrates that anyone can access, anywhere in the country, with only pen and paper.

Understorey: A Year Among Weeds, by Anna Chapman Parker. Published by Duckworth, June 2024. Reviewed by Coreen Grant.

Other books we read this month

What the Wild Sea Can Be: The Future of the Ocean, by Helen Scales, is a tour of hope and despair through the key threats facing the life in our oceans and what could be done to overcome them – or at least blunt their worst impacts in the coming years. Despite rattling through various topics at pace, the book acts an engaging primer, and is full of titbits of the latest astounding findings by marine scientists. -CL

The Accidental Garden: Gardens, Wilderness and the Space in Between, by Richard Mabey, details the veteran nature writer's journey to create a semi-domestic space where nature can thrive, based upon the history of the Norfolk landscape where he lives. Full of wisdom and insight, this is as much a memoir and an exploration of what it means to write about nature as it is the story of his garden. -SY

The Heart of the Woods, by Wyl Menmuir, describes how modern-day humans continue to coexist with woodlands, despite millennia of deforestation. Menmuir has travelled widely and uncovered a variety of working and spiritual encounters; his writing relies heavily on the words of the people he meets. At a time when woodland coverage is desperately low, this book is a reminder that it is still possible to have a relationship with the trees. -SY

Reviewed by Sophie Yeo and Chantal Lyons.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.